|

Climate Justice Now!

| Why Tree Planting is Not the Answer to Climate Change

|

Sunday, November 27, 2005 |

Fossil Carbon vs. Forest Carbon:

Two Environmental Historians Speak "Carbon cannot be sequestered like bullion. Biological preserves are not a kind of Fort Knox for carbon. Living systems store that carbon, and those terrestrial biotas demand a fire tithe. That tithe can be given voluntarily or it will be extracted by force. Taking the carbon exhumed by industrial combustion from the geologic past and stacking it into overripe living woodpiles is an approach of questionable wisdom . . . "Eliminate fire and you can build up, for a while, carbon stocks, but at probable damage to the ecosystem upon the health of which the future regulation of carbon in the biosphere depends. Stockpile biomass carbon, whether in Yellowstone National Park or in a Chilean eucalyptus plantation, and you also stockpile fuel, the combustion equivalent of burying toxic waste. Refuse to tend the domestic fire and the feral fire will return -- as it recently did in Yellowstone and Brazil's Parc Nacional das Emas, where years of fire exclusion ended with a lightning strike that seared 85 per cent of the park in one fiery flash." --Stephen J. Pyne, Arizona State University, author of Vestal Fire "Undeniably, having more trees will work in the right direction but to a minute degree. For its practical effect, telling people to plant trees is like telling them to drink more water to keep down rising sea-levels." --Oliver Rackham, Cambridge University, author of A History of the Countryside

by: ProfMKD @ 11:05 pm

|

| CARBON PROJECT Q & A: Sri Lanka, renewables and semi-slavery (sixth in a series)

|

Sri Lanka: A “Clean Energy” Project that was not So Clean Extracted from the research of Cynthia Caron

Today’s smart business money is going into buying carbon credits from projects that seem particularly meaningless when it comes to addressing climate change: projects to destroy industrial gases or landfill methane and the like. These are the cheapest credits and they can be obtained with the least trouble.

But there do exist, after all, carbon projects that promote energy efficiency or renewable energy technologies. The Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism has dozens of such schemes in its pipeline, although they generate only a miniscule proportion of total credits. Some of these projects are even small and community-based. So far, however, such projects are merely a bit of expensive window-dressing for the big industrial projects generating cheaper credits. In a competitive market, they appear to have little future. But are such projects always desirable even on their own terms? For example, are all renewable energy projects good just because they can be described with the word “renewable”? -- Q. I don’t understand. What could possibly be wrong with promoting renewable energy? It’s not that renewable energy technologies are inherently good or bad. It all depends on how they are used. Let’s take, for example, one of the world’s very first attempts to “compensate for” or “offset” industrial carbon-dioxide emissions — a rural solar electrification programme in Sri Lanka. The story, as told by Cynthia Caron, begins in 1997, when the legislature of the US state of Oregon created a task force that later legally required all new power plants in the state to offset all of their carbon dioxide emissions. When companies put in bids for the contract to build a new 500-megawatt, natural-gas fired power station in Klamath Falls, they therefore also had to present plans for “compensating” for its CO2 emissions. The winner of the contract, PacificCorp Power Marketing, proposed a diversified US$4.3 million dollar carbon-offset portfolio allocating $3.1 million to finance off-site carbon mitigation projects. In particular, the firm put US$500,000 into a revolving fund to buy photovoltaic (solar-home) systems and install them in “remote households without electricity in India, China and Sri Lanka”. In 1999, PacificCorp Power and the City of Klamath Falls signed the necessary finance agreement with a US solar-energy company called the Solar Electric Light Company, or SELCO. In all, SELCO agreed to install 182,000 solar-home systems in these three Asian countries, 120,000 in Sri Lanka alone. The idea was that the solar systems would reduce the carbon dioxide emissions given off by the kerosene lamps commonly used in households that are “off-grid”, or without grid-connected electricity. On average, SELCO calculated, each such household generates 0.3 tons of carbon dioxide per year. SELCO argued that the installation of a 20 or 35-watt solar-home system would displace three smoky kerosene lamps and a 50-watt system would displace four. Over the next thirty years, it claimed that these systems would prevent the release of 1.34 million tons of carbon into the atmosphere, entitling the Klamath Falls power plant to emit the same amount. -- Q. So what’s the problem? It sounds like a win-win situation. The Klamath Falls plant makes itself “carbon-neutral”, while deprived Asian households get a new, clean, green, small-scale source of energy for lighting! Not quite. Aside from the fact that such projects can’t, in fact, verify that they make fossil fuel burning “carbon-neutral” (see "Global Warming and the Ghost of Frank Knight", previous post), the benefits to the South that carbon offsetting promises don’t necessarily materialize, either. -- Q. Why not? The first thing to remember is that just as industries in the North have historically relied on the environmental subsidy that cheap mineral extraction in the South has provided, in this project a Northern industry used decentralized solar technology to reorder off-grid spaces in the South into spaces of economic opportunity that subsidize their costs of production through carbon dioxide offsetting. Essentially, once again, the South is subsidizing production in the North – but this time not through a process of extraction, but through a process of sequestration. -- Q. You’ll have to explain that to me. Traditionally, fossil fuel extraction has resulted in the overuse of a good which cannot be seen – the global carbon sink. And the inequality in the use of that sink between North and South has been invisible. Now, however, that inequality is becoming more visible within certain landscapes in the form of physical and social changes like those associated with the PacificCorp/SELCO project. The solar component of the Klamath Falls plant, in essence, proposed to “mine” carbon credits from off-grid areas in Sri Lanka. However, the existence of these off-grid areas is partially due to social inequalities within Sri Lanka. In this case, the project was taking advantage of one particularly marginalized community of Sri Lankan workers in order to support its own disproportionate use of fossil fuels. -- Q. Well, maybe. But so what? PacificCorp didn’t create the inequalities in resource use that it was going to benefit from. Why should it be up to PacificCorp to solve social problems in Sri Lanka? Besides, aren’t we in danger of making the best the enemy of the good here? PacificCorp may have wanted to use this project to go on using a lot of fossil fuels, but at least the Sri Lankan workers got a little something out of the deal to improve their lifestyles. Well, as a matter of fact, that really wasn’t the case, either. In practice, the PacificCorp/SELCO arrangement in Sri Lanka wound up supporting what one Sri Lankan scholar-activist, Paul Casperz, calls a feudal system of “semi-slavery” on plantations. -- Q. Semi-slavery? Aw, come on! Aren’t you being a bit inflammatory? How could decentralized, sustainable solar power possibly have anything to do with that? Solar power didn’t create the problem, of course. But interventions like like this one in the estate sector often have a way of helping perpetuate them (just as in Los Angeles in recent times, pollution trading has entrenched existing environmental injustices). The trick, as so often in the world of development and environment, is to understand that a bit of technology is never “just” a neutral lump of metal or a piece of machinery benignly guided into place by the intentions of its providers, but winds up becoming different things in different places. In Sri Lanka, the kerosene-lamp users that PacificCorp/SELCO ended up targeting earned their living in what is known as the “estate” or tea plantation sector. This is a sector in which nearly 90 per cent of the people are without grid-connected electricity, compared to 60 per cent of the non-estate rural sector and only five per cent of urban dwellers being off-grid. (In all, at the time of the project 48 percent of Sri Lanka’s population of 18.5 million was off-the-grid.) A large proportion of this off-grid population was – and is – from the minority Estate Tamil community,7 which lives and works in conditions of debt dependence on tea and rubber plantations established by the British during the colonial period. Unfair labor practices in the sector have continued to keep estate society separate from and unequal to the rest of Sri Lankan society. Daily wages average US$1.58 and the literacy rate is approximately 66 per cent, compared to 92 per cent for the country as a whole. The estate population is underserved when it comes to infrastructure. A sample survey of fifty estates found that 62 per cent of of estate residents lacked individual latrines and 46 per cent did not have a water source within 100 meters of their residence. Due partly to its cost, electrification, unlike health care, water supply, and sanitation, has never been one of the core social issues that social-service organizations working among the estate population get involved in. -- Q. That would seem to make the estate sector the perfect choice for a solar technology project. I still don’t see the problem. There’s no question that electrification could do a lot of good for workers and their families. By displacing smoky kerosene lamps, it would provide a smoke-free environment that reduces respiratory aliments, as well as quality lighting that reduces eyestrain and creates a better study environment for the school-going generation who are eager to secure employment outside the plantation economy. Researchers have found clear connections between off-grid technology and educational achievement. As tea estates are regulated and highly structured enclave economies, SELCO could not approach workers without the cooperation and approval of estate management. The CEO of one plantation corporation, Neeyamakola Plantations, was willing to allow SELCO access to “the market” that his off-grid workers represented. He himself liked the idea of solar electrification, but for an entirely different set of reasons. -- Q. How’s that? Sri Lanka’s 474 plantation estates recently were privatized. Facing fierce competition from other tea-producing countries, they need to lower production costs and increase worker productivity in order to compensate for low tea prices on the global market andwage increases mandated by the Sri Lankan Government. Neeyamakola had already introduced some productivity-related incentives and thought that solar-home systems could provide another. After all, with a regular electricity supply, workers could watch more television. Seeing how other people in the country lived, they’d want to raise their standards of living too. For that, they’d need money. To earn more money, they’d work harder or longer, or both. So, in 2000, Neeyamakola was only too happy to sign an agreement with SELCO for a pilot project on its Vijaya rubber and tea estate in Sri Lanka’s Sabaragamuwa Province, where over 200 families lived. -- Q. Well, it sounds to me like the perfect match. If Neeyamakola focused on the bottom line, what’s so bad about that? It’s a matter of unleashing the profit motive for the incremental improvement of society and the environment. No one expected Neeyamakola, SELCO or PacificCorp to operate as charities. The point is to understand whether such a business partnership was ever capable of doing the things it was advertised to do, what effects the partnership had on the affected societies, and who might be held responsible for the results. -- Q. So what happened? At first, the pilot project was to be limited to workers living in one of the four administrative divisions into which the Vijaya estate was divided, Lower Division, and in nearby villages. Some four-fifths of these workers were Estate Tamils living in estate-provided “line housing”. The other fifth were Sinhalese who lived within walking distance. In the first three months, only 29 families decided to participate in the solar electrification project: 22 of Lower Division’s 63 families and seven Sinhala workers who lived in adjacent villages. In the end, the project installed only 35 systems before it was cancelled in 2001. -- Q. What went wrong? Two things. The first thing that happened was that, in the historical and corporate context of the estate sector, the SELCO project wound up being structured in a way that strengthened the already oppressive hold of the plantation company over its workers. -- Q. But how could that happen? Solar energy is supposed to make people more independent, not less so. This gets back to the nature of Neeyamakola as a private firm. From the perspective of plantation management, the electrification project had nothing to do with carbon mitigation and everything to do with profitability and labor regulation. Neeyamakola’s concern was to increase productivity. Its idea was to use access to loans for solar-home systems to entice estate laborers into working additional days. The Neeyamakola accounting department would deduct a Rs.500 loan repayment every month and send it to SELCO. In order to qualify for a loan, workers had to be registered employees who worked at least five days a month on the estate. The loan added another layer of worker indebtedness to management. In this case, the indebtedness would last the five years that it would take the worker to repay the loan taken from the corporation. From workers’ point of view, the system only added to the company’s control over their lives. Historically, after all, the only way that estate workers have been able to get financing to improve their living conditions has been through loans that keep them tied to the unfair labor practices and dismal living conditions of estate life. To upgrade their housing, for instance, workers have to take out loans from the Plantation Housing and Social Welfare Trust (PHSWT). One condition of these loans is that “at least one family member of each family will be required to work on the plantation during the 15-year lease period”, during which estate management takes monthly deductions from wages. Hampered by low pay and perpetual indebtedness, workers find it difficult move on and out of the estate economy. -- Q. I see. And what’s the second problem? Inequality and social conflict of many different kinds. First, as Neeyamakola offered solar primarily to estate workers, most of whom are members of the Tamil ethnic minority, the nearby off-grid villagers of the Sinhalese majority felt discriminated against and marginalized. Disgruntled youth from adjacent villages as well as from estate families who weren’t buying solar systems threw rocks at the solar panels and otherwise tried to vandalize them. Second, local politicians and union leaders saw solar electricity as a threat to their power, since both groups use the promise of getting the local area connected to the conventional electricity grid as a way of securing votes. So they started issuing threats to discourage prospective buyers. Third, the village communities living around the Vijaya Estate feared that if too many people on the estate purchased solar, the Ceylon Electricity Board would have a reason for not extending the grid into their area. And without the grid, they felt, that small-scale industry and other entrepreneurial activities, that would generate economic development and increased family income, would remain out of reach, making their social and economic disadvantages permanent. (Any delay in the extension of the grid to the area occasioned by the PacificCorp/SELCO Neeyamakola project, of course, would have its own effects on the use of carbon, and would have to be factored into PacificCorp/SELCO’s carbon accounts. There is no indication that this was done.) Added to all of this was inequality within the community of estate workers themselves. One consequence of Neeyamakola’s focus on getting more out of its workers was that many estate residents whose work is productive for society in a wider sense were ineligible for the systems. One example is what happened to the primary school teacher in the Tamil-medium government school that served the estate population. The daughter of retired estate workers, the teacher received a reliable monthly salary, could have met a monthly payment schedule, and was willing to pay, but was ineligible for a system because her labor was not seen as contributing directly to the estate’s economic productivity and profit margin. Retired estate workers and their families were excluded for the same reason. SELCO, a firm new to Sri Lanka, was unable to ensure community-wide benefits or equity within the community as a pre-requisite in the design of the pilot project. On the Vijaya Estate, in short, the decentralized nature of solar power – in other contexts a selling point for the technology – had quite another impact and meaning in the context of Sri Lanka’s estate sector. It provided the company that was controlling the “technology transfer” with a new technique to exert control over its labor force and ensure competitive advantage, while exacerbating underlying conflicts over equity. It’s interesting to note, incidentally, that solar projects in Sri Lanka often fall short even at the household level, where many families end up reducing their consumption of kerosene by only 50 per cent. There are many reasons for this. Kerosene use is necessary to make up for faulty management while household members become acquainted with the energy-storage patterns of the battery and system operation. Households also face problems managing stored energy, with children often using it all up watching afternoon television. And local weather patterns and topography likewise take their toll. In some hilly areas with multiple monsoons, solar can supplement kerosene systems at best for a six- to nine-month period depending on the timing and duration of the monsoon. -- Q. Did PacificCorp’s electricity customers – or the Oregon legislature – know about all this? Given the geographical and cultural distances involved, it would have been difficult for them to find out. On the other hand, it seems unlikely that Northern consumers of electricity – if they are informed of such details – will accept carbon-offset projects that involve not only dubious carbon accounting, but also blatantly exploitative conditions and the reversal of poverty alleviation efforts. This is another reason why, while undertakings like PacificCorp/SELCO’s have from the beginning been more about “preserving the economic status quo” and promoting cost efficiency in developed countries than about bringing equity to developing countries, it is unclear how long they will be able to work even in maintaining that status quo. -- Q. OK, I can see there were some problems. But surely social and environmental impact assessments could have identified some of these problems in advance. With proper regulation, they could then have been prevented. Some of them might have been. For example, the solar technology could have been reconfigured so that an entire line of families could have pooled resources and benefited, rather than just individual houses. But setting up an apparatus to assess, modify, monitor and oversee such a project isn’t by itself the answer. Such an apparatus, after all, would have brought with it a fresh set of questions. Who would have carried out the social impact assessment and would they have been sensitive to local social realities? Would its recommendations have been politically acceptable to Neeyamakola? Would its cost have been acceptable to PacificCorp? What kind of further oversight would have been necessary to prevent it from merely adding legitimacy to a project whose underlying problems were left untouched? Just as a technology is never “just” a neutral piece of machinery which can be smoothly slotted into place to solve the same problem in any social circumstance, so the success of a social or environmental impact assessment is dependent on how it will be used and carried out in a local context. -- Q. But if success is so dependent on political context, how will it ever be possible for new renewable technologies to make headway anywhere? If it isn’t possible, then we might as well give in and keep using fossil fuel technologies! We might as well go along with ExxonMobil when they claim that we have to go on drilling oil since anything else would be to betray the poor! The alternative is not to accept the dominance of fossil fuel technologies. Their continued dominance also does nothing to improve the position of disadvantaged groups such as Sri Lanka’s Estate Tamils. Nor is the alternative simply to accept the system of global and local inequality exemplified in Sri Lanka’s estate plantation sector. The alternative, rather, is to act using our understanding that what keeps marginal communities like that of Sri Lanka’s Estate Tamils in the dark, so to speak, is not just bad machines, or just a lack of good ones, but also a deeper pattern of local and global politics. Cutting fossil fuel use means understanding this deeper pattern. Up to now, climate activists and policymakers have often told each other that “the essential question is not so much what will happen on the ground, but what will happen in the atmosphere”.22 The example of the PacificCorp/SELCO/Neeyamakola rural solar electrification project helps show why this is a false dichotomy. What happens on the ground in communities affected by carbon projects is important not only because of the displacement of the social burdens of climate change mitigation from the North onto already marginalized groups in the South, but also because what happens on the ground influences what happens in the atmosphere.

------------------------------------------------------ This section is based on the research of Dr Cynthia Caron. After completing her Ph. D. at Cornell University, USA, on electricity sector restructuring in Sri Lanka, Dr Caron moved to Sri Lanka. She has been awarded a grant from the Macarthur Foundation and has been researching forced migration, resettlement and Muslim nationalism and its relation with Sri Lanka's ethnic conflict, as well as working on development and health projects.

by: ProfMKD @ 3:01 pm

|

| CARBON PROJECT Q & A: India -- a Taste of the Future (fifth in a series)

|

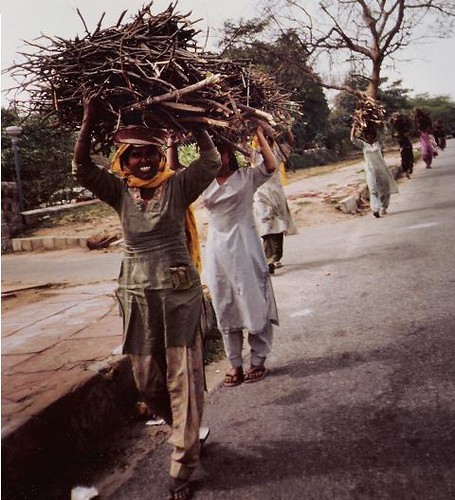

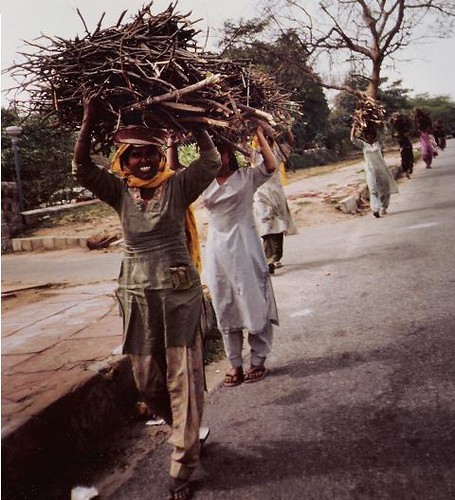

India: A Taste of the Future Extracted from research by Emily Caruso, Vijaya Bhaskara Reddy, Yakshi Shramik, Adivasi Sangathan, the Centre for Science and Environment and others

If countries in Latin America pioneered carbon projects, one of the countries that has attracted the greatest longer-term interest among Northern carbon traders and investors is India. The interest is reciprocated by many in India’s government. Three of the first dozen or so CDM projects to be registered – an HFC-231 destruction project, a small hydropower project, and a biomass project – are located in India. The country is currently is second only to Brazil in volume of CDM credits in the pipeline, although China, Mexico, Argentina and Chile are also prominent. As elsewhere, most of the money would go to end-of-pipe projects that destroy non-carbon-dioxide greenhouse gases. According to the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment, some 77 per cent of Indian CDM credits currently in the pipeline would be derived from projects which destroy HFCs, which are extremely powerful greenhouse gases used in refrigeration, air conditioning, and industrial processes (Ritu Gupta, Shams Kazi and Julian Cheatle, “Carbon Rush”, Down to Earth, Centre for Science and Environment, 15 November 2005). Inevitably, social activists are raising questions about whether such projects provide “any credible sustainable development” to local communities. -- Q. Why shouldn’t such projects be beneficial to local communities? First, because HFCs are so bad for the climate, projects that destroy them can generate huge numbers of lucrative credits merely by bolting a bit of extra machinery onto an existing industrial plant. As a result, there are no knock-on social benefits other than providing income for the machinery manufacturer and some experience for a few technicians. Second, such projects don’t help society become less dependent on fossil fuels. They don’t advance renewable energy sources, and they don’t help societies organize themselves in ways that require less coal, oil or gas. Third, by ensuring that the market for credits from carbon projects is dominated by large industrial firms, they make it that much more difficult for renewable energy or efficiency projects to get a foothold. -- Q. But don’t such projects also provide perverse incentives for governments not to do anything about pollution except through the carbon market? After all, if I were a government trying to help the industries in my country get masses of carbon credits from destroying a little bit of HFCs, I would hesitate to pass laws to clean up HFCs. After all, such laws wouldn’t make industry any money. In fact, they would cost industry money. Instead, why not just allow the pollution to go on until someone comes along offering money if it is cleaned up? That’s a question that’s understandably going through the minds of government officials in many Southern countries. As a result, it’s not clear whether the CDM market is actually a force for less pollution or not. -- Q. But at least such projects don’t do any harm to local people, right? That’s a matter of opinion. If the industry getting the credits is hurting local people, local people may well disagree with the project. Near Gujarat Flourochemicals Limited, one of India’s first projects to be registered with the CDM, villagers complain of air pollution’s effects on their crops, especially during the rainy season, and believe the plant’s “solar oxidation pond” adds to local water pollution. Of course, theirs are not the only voices. D. K. Sachdeva, a vice president of the company, insists locals’ claims were politically motivated. “As we are the only factory in this area, people make allegations to make money,” he asserted. Meanwhile, villagers near another factory hoping to benefit from CDM credits, Rajasthan’s SRF Flourochemicals, believe that their aquifers are being depleted and their groundwater polluted, leading to allergies, rashes, crop failures, and a lack of safe drinking water. -- Q. What about smaller projects – the ones that don’t generate so many credits? Are there any local objections to them? Some of the many biomass carbon projects planned for India are also rousing local concerns. One example is the 20-megawatt RK Powergen Private Limited generating plant at Hiriyur in Chitradurga district of Karnataka, which is currently preparing a Project Design Document for application to the CDM. According to M. Tepaswami, a 65-year-old resident of nearby Babboor village, RK Powergen is responsible for serious deforestation. “First, the plant cut the trees of our area and now they are destroying the forests of Chikmangalur, Shimoga, Mysore and other places. They pay Rs 550 per tonne of wood, which they source using contractors. The contractors, in turn, source wood from all over the state.” Another villager claimed that “poor people find it difficult to get wood for cooking and other purposes.” Jobs promised by the firm, Tepaswami complains, were in the end given to outsiders. Employees at the Karnataka Power Transmission Corporation meanwhile claim that its “equipment is adversely affected due to the factory’s pollution”, while local villagers complain of reduced crop yields and plunging groundwater levels. Again, predictably, project managers deny the allegations. “If there is deforestation,” said plant manager Amit Gupta, “then local people are to be blamed because they are supplying the wood to us” (Gupta, Kazi, Cheatle in Down to Earth [see above]). But such disputes may be a sign of things to come. -- Q. What about plantation projects and other forestry “sink” projects? Are they also running into trouble? Currently, no legal framework to deal with CDM carbon forestry exists, so proposals for such projects are on hold. But carbon forestry is definitely on the cards for India. The World Bank and forestry and private sector interests are studying, experimenting with and promoting a number of ideas. A National Environment Policy Draft circulated by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) in 2004 confirms a new, “liberalized” environmental policy that promotes carbon trading and other environmental services trades. The move toward carbon forestry also chimes with a grandiose existing plan on the part of the MoEF to bring, by 2020, 30 million hectares of “degraded” forest and other lands under industrial tree and cash crop plantations, in collaboration with the private sector. Among the scores of CDM and other carbon projects being contemplated for India are forestry projects in Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh states. Here, an organization called Community Forestry International (CFI) has been surveying opportunities for using trees to soak up carbon. CFI helps “policy makers, development agencies, NGOs, and professional foresters create the legal instruments, human resource capacities, and negotiation processes and methods to support resident resource managers” in stabilizing and regenerating forests. Its work in Madhya Pradesh has been supported by the US Agency for International Development and the US Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service. CFI’s work in Andhra Pradesh, meanwhile, has been financed by the Climate Change and Energy Division of Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. CFI suggests that, in India, the CDM would be a viable income-generating activity for rural indigenous communities. But there are strong reasons to doubt this. -- Q. Why? In India, as everywhere else, it’s not abstract theory, but rather the institutional structure into which CDM would fit, that provides the key clues both to its likely social outcome and to its likely climatic outcome. Take, for example, a CDM scheme investigated by CFI that would be sited in Harda district, Madhya Pradesh state. Here CFI sees CDM’s role as providing financial support for an institution called Joint Forest Management (JFM). -- Q. What’s that? Joint Forest Management (JFM) is supposed to provide a system for forest protection and sustainable use through the establishment of Village Forest Protection Committees (VFPCs), through which government and development aid funds are channelled for ‘forest management’ and village-level development works. Formalised by state governments and largely funded by the World Bank, Joint Forest Management (JFM) was designed partly to ensure that forest-dependent people gain some benefit from protecting the forests. It’s already implemented in every region of India. Long before carbon trading was ever conceived of, JFM had become an institution used and contested by village elites, NGOs, foresters, state officials, environmentalists and development agencies alike in various attempts to transform commercial and conservation spaces and structures of forest rights for their respective advantages (see K. Sivaramakrishnan, “'Modern Forestry: Trees and Development Spaces in West Bengal”, in Laura Rival, (ed.), The Social Life of Trees: Anthropological Perspectives on Tree Symbolism, Oxford: Berg, pp. 273-96). -- Q. So there should be a lot of evidence already for whether it works or not. Yes, but there’s not much agreement about what that evidence means, or for whom JFM works and in what way. CFI sees the JFM programme as having improved the standard of living in Adivasi villages, as well as their relationship with the Forest Department. It also found that JFM had helped regenerate forests in Rahetgaon Forest Range, resulting in higher income for Village Forest Protection Committees, although admitting that in Handia Forest Range, social conflicts had resulted in decreased JFM-related investment by the Forest Department and less positive outcomes. CFI thinks that for JFM to expand its role on India’s forest land would be “both desirable and necessary” (see Mark Poffenberger, N. H. Ravindranath, D. N. Pandey et al., Communities and Climate Change: The Clean Development Mechanism and Village-based Forest Restoration in Central India, Community Forestry International and Indian Institute of Forest Management, Santa Barbara, 2001, p. 71, available at http://www.communityforestryinternational.org/publications/research_reports/harda_report_with_maps.pdf). On the other hand, many indigenous (or Adivasi) community members, activists and NGOs see JFM as a system which further entrenches Forest Department control over Adivasi lands and forest management, although the practices of different village committees vary. Mass Tribal Organisations, forest-related NGOs and academics have published evidence that JFM Village Forest Protection Committees (VFPCs), composed of community members, function principally as a local, village-level branch and extensions of state forest authority. Communities interviewed in Harda in 2004 said that VFPC chairmen and committee members have become to a large extent “the Forest Department’s men”. -- Q. What’s wrong with that? These local JFM bodies are accused of imposing unjust and unwanted policies on their own communities, of undermining traditional management systems and of marginalising traditional and formal self-governing local village authorities. In one Madhya Pradesh case, forest authorities and the police shot dead villagers opposing JFM and VFPC policies, in an echo of hostilities between the Forest Department and various classes of other forest users that go back a century. According to many Mass Tribal Organisations, communities and activists, JFM was effectively imposed on them without appropriate consultation during project identification, planning and implementation, and has resulted in the marginalisation, displacement and violation of the customary and traditional rights of the Adivasis in the state.14 Contrary to MoEF circulars issued in the 1990s regarding regularisation of lands cultivated by Adivasis and settlement of land disputes, many state governments implemented JFM programmes on disputed lands. JFM has been implicated in involuntary resettlement of forest “encroachers”, resulting in many Adivasis losing land and access to essential forest goods. Current problems with JFM in Madhya Pradesh, according to many local people and activists, include: * Conflicts within communities as a result of economic disparities between VFPC members and non-members. * Conflicts between Adivasi groups and other communities generated by the imposition of VFPC boundaries without reference to customary village boundaries. * Curtailment of nistar rights (customary rights to local natural goods). * Conflicts over bans on grazing in the forest and on collecting timber for individual household use. * Indiscriminate fining. According to some Harda activists, JFM has opened deeper rifts within and between Adivasi villages and between different Adivasi groups, and has engendered conflict between communities and the Forest Department. Although funding for the local JFM scheme is now exhausted, VFPCs are still in place in many villages, recouping salaries from the interest remaining in their JFM accounts and from fines imposed on members of their own and neighbouring communities. Communities interviewed also claim that VFPC financial dealings are not transparent. In July 2004, non-VFPC villagers in Harda reported that they would like to see funding for VFPCs stopped and, ultimately, the committees disbanded; and would also like to see forest management returned to them and their rights to their traditional lands and resources restored.15 That’s not to say there are not other stories about JFM and the forest protection committees, which are institutions whose meaning and functions are competed over among many conflicting groups inside and outside villages. It is merely to emphasize that, in the words of University of Washington anthropologist K. Sivaramarkishnan, “when environmental protection is to be accomplished through the exclusion of certain people from the use of a resource, it will follow existing patterns of power and stratification in society.” -- Q. So maybe these embattled Village Forest Protection Committees are not the ideal bodies to carry out CDM carbon projects. That would be an understatement. CFI’s proposal that, in order to reduce transaction costs, a federation of VFPCs ought to be created in the Handia range to carry out a pilot carbon offset project is also questionable. Equally dubious is CFI’s suggestion that the Forest Department should adjudicate cases of conflict there, a statement that many people in the communities interviewed would find unacceptable. -- Q. If there are all these problems, why didn’t the CFI studies detect them? Much of the data used in the CFI studies came from the Forest Department and possibly discussions with VFPC members rather than from independent field work with communities and non-VFPC community members. Significantly, both MoEF and the Madya Pradesh forest department were supporting agencies for the CFI study. -- Q. But it seems there could be an even more fundamental problem. If JFM projects are going forward anyway, even without the CDM, they’re not saving carbon over and above what would have been saved anyway. So how could they generate credits? That’s not clear. JFM has been implemented in Madhya Pradesh since 1991 and so hardly qualifies as a new project. But there are plenty of other problems with CFI’s carbon sequestration claims as well. For example, CFI doesn’t take into account the changes in numbers of people and in community and family composition to be expected over the project’s 20-25 year lifetime. CFI’s estimates of fuelwood carried out by communities in the Rahetgaon range are also inaccurate. CFI believes every family uses two head loads of fuelwood per week, but recent interviewees suggested that a more realistic figure would be 18-22, especially during the winter and the monsoon season. CFI also makes the questionable assumption that local communities would relinquish their forest-harvesting activities for the sake of very little monetary income from carbon sales, and that income flowing to VFPCs would be transparently distributed. In order to assess how much carbon would be saved, CFI compared vegetation in forest plots at different stages of growth and subject to different kinds of pressure from humans. Yet while the total area of forest to be considered is 142,535 ha, the total number of 50m x 50m plots assessed was 39, representing a total study area of only 9.75 ha. That may be an adequate sample in biological terms. But it’s hardly enough to assess the range of social influences on carbon storage in different places. -- Q. Have any prospective carbon forestry projects been looked at in other parts of India? Many. To take just one more nearby example, in Adilabad, Andhra Pradesh state, CFI saw possibilities of sequestering carbon by reforesting and afforesting nonforest or “degraded” forest lands whose carbon content has been depleted by a large and growing human and cattle population, uncontrolled grazing of cattle in forests and ‘encroachment’ on and conversion of forest lands for podu (swidden) cultivation. The best option, CFI felt, would be to regenerate teak and mixed deciduous forests. Clonal eucalyptus plantations would, it thought, accumulate carbon faster, and would have other commercial uses such as timber and pulp, as well as incremental returns for any interested investor, but would cost more to establish and maintain, and would be sure to be condemned by Adivasi communities and activists as a new form of colonialism. -- Q. So who would carry out these regeneration projects? Here CFI came to a different conclusion than in Madhya Pradesh. In Andhra Pradesh, it decided, the best agencies for taking on forest regeneration would be Women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs). -- Q. Which are what? SHGs were set up by the state-level Inter-Tribal Development Agency during the 1990s as a mechanism for improving the finances of households through micro-credit schemes and capacity-building, as well as linking households with financial institutions and government authorities. CFI says that they’re much more dynamic, accountable and transparent than other local institutions, such as Forest Protection Committees (known as Vana Samrakshana Samithi or VSS in Andhra Pradesh), which are viewed as inefficient, untransparent, untrustworthy, and troubled in their relationship with the Forest Department. -- Q. Sounds perfect. Except that it’s hard to see how the virtues of the Women’s Self-Help Groups could work for the carbon economy. For one thing, CFI states that only if the SHGs come together in a federation would carbon offset forestry projects be financially viable, given the high transaction costs involved in preparing and carrying them out. Yet it does not explain how such a federation could come about among rural communities, nor how SHGs could become involved in CDM projects and link themselves to the carbon market. Nor does it mention that SHGs currently work in relative isolation from the Panchayat Raj institutions (the ultimate village-level formal self-governing authority in rural India), the Forest Department and local Forest Protection Committees. In addition, the income families would receive from carbon – 150 rupees per month for protecting 1.5 ha of forest, according to CFI – is less than they get from other forms of forest use. While CFI estimates the total cost of a 2000-hectare CDM project covering 20 villages in Adilabad as US$270,000, it is difficult to imagine how such small areas of forest regeneration could provide enough carbon to provide reasonable and usable benefits to the communities. Moreover, few Adivasi communities have exclusive rights to the extensive area of 250 ha of “degraded” land envisaged by CFI. If instituted near Adivasi communities, CDM projects would likely eat up land elsewhere, including Forest Department land. And if podu lands are excluded from CDM use, the potential for reforestation would be reduced to 10 per cent of the total forest area. -- Q. Well, assuming there are some problems with these preliminary ideas about how carbon projects might be implemented in the Indian countryside, surely there’s nothing to worry about yet. After all, these are only a few studies done by a single organization. We’ll have to learn as we go along. The problem is that the mere fact that studies like CFI’s are being carried out already gives legitimacy to the idea of using carbon offsets in the South, as well as other ‘flexible mechanisms’, to tackle climate change. Nor are CFI’s studies the only ones claiming that Joint Forest Management provides a sound basis for carbon forestry projects. International research institutions such as the Centre for International Forestry, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research and various academics have done the same. The World Bank, too, funds JFM, is heavily involved in the global carbon market, and is currently seeking to increase funding of forestry projects in India – not a reassuring sign. -- Q. Still, what you’ve been talking about are problems with JFM, not with carbon offset trading as such. Whether or not JFM is involved, some Indian activists fear that by creating a market for carbon, CDM projects will engender change in the relationship between Adivasis and their lands and forests. Access and ownership rights are likely to be transformed into benefit-sharing and stakeholder-type relationships. Adivasi communities may lose their capacity to sustain food security, livelihoods, and fundamental social, cultural and spiritual ties. Long before JFM came along, Indian government agencies, Indian government agencies were referring to much of the livelihood land base of many indigenous and forest-dependent peoples as unowned or unused “wasteland” or “degraded land”. They still do. International financial institutions, northern governments and even international research institutions use similar language in their documents. In Andhra Pradesh, the state government, currently promoting Pongamia plantations, proposes establishing up to three million hectares of new plantations on so-called “common land” (or “waste land”) throughout the state. CDM afforestation projects can be established on lands that have not been forested for 50 years, and reforestation projects on lands that have not been forested for 15 years. Such projects could have serious consequences for Adivasi peoples practicing swidden cultivation on government forest land or in “forest villages”. CDM projects would also have an incentive to seek repression of any Adivasi livelihood activities that they displace that could result in increased releases of carbon elsewhere, since such releases would have to be debited from project carbon accounts. Cattle grazing, fuelwood cutting and clearing of new areas for swidden cultivation could all fall into this category. Also, while CDM plantations are one cause of concern among indigenous communities, forest conservation projects are also on the horizon. Although conservation schemes are not yet eligible for CDM, conservation financiers and the World Bank and Global Environment Fund are increasingly promoting the idea of protected areas as an additional source of carbon credits. Indigenous peoples will clearly be in for a fight should carbon sequestration and protected area projects come together on their territories. In order to avoid conflict, in addition, any CDM project proponent will need to clarify who owns the land, the project and the carbon. This immediately militates against Adivasi peoples, since in India, the government claims formal ownership and control over indigenous lands and resources. In this and other ways, it is unclear how CDM projects could do anything but further entrench discrimination against Adivasi communities by government authorities and rural elites. -- Q. But isn’t it true that in international law and best practice, indigenous land and resource rights must be respected in all development projects? Isn’t free, prior and informed consent starting to be a universal requirement for such schemes? That’s the theory. The reality is different. CDM has so far shown no sign of doing anything but going along with prevailing practice.

----------------------------------------- Will Carbon Forestry Exclude People from Their Land? Some Cautionary Voices “Joint Forest Management and Community Forest Management are being used as tools to exclude the Adivasis from their survival sources, and are compelling them to slip into poverty and migrate in search of work. Instead of . . . recognising Adivasi rights to the forest, the government is seeking their eviction through all possible means.”

--Local activist “Government figures show that there are about 5 crores (50 million) hectares of ‘waste land’ in India, land which . . . now lies open to exploitation through carbon forestry schemes. What the central government does not say is that most of this ‘waste land’ belongs to Adivasis and other forest dependent communities, who will be the first to lose out from the development of such schemes.”

--Madhya Pradesh activist “If large protected areas or plantations are managed for long-term carbon sequestration and storage, local people may lose access to other products such as fibre or food. . . . governments and companies are best placed to benefit from such schemes. . . . the frequently weak organization (or high transaction costs of improving organization) of the rural poor and landless will reduce their access to the carbon offset market, particularly given the many complex requirements of carbon offset interventions. Other barriers to the involvement of rural people centre on their prevailing small-scale and complex land use practices, without clear tenure systems.” --Stephen Bass (Rural Livelihoods and Carbon Management, IIED, London, 2000)

------------------------------------------------

-----------------------------------------

From a forthcoming issue of Development Dialogue. For more information: larrylohmann@gn.apc.org.

by: ProfMKD @ 2:20 pm

|

|

Global Warming and the Ghost of Frank Knight

Frank H. Knight (1885-1972), a University of Chicago economist recognized as one of the deepest thinkers in 20th century US social science, is famous for his distinction between risk and uncertainty. Although he could never have anticipated all the ways it could be applied, Knight's 1921 distinction helps explain why it is confused to put any faith in a market for emissions credits generated by carbon-saving projects.

Risk, in Knights sense, refers to situations in which the probability of something going wrong is well-known. An example is the flip of a coin. There is a 50-50 chance of its being either heads or tails. If you gamble on heads, you risk losing your money if it turns out to be tails. But you know exactly what the odds are.

Uncertainty is different. Here, you know all the things that can go wrong, but cant calculate the probability of a harmful result. For example, scientists know that the use of antibiotics in animal feed induces resistance to antibiotics in humans, but cant be sure what the probabilities are that any particular antibiotic will become useless over the next 10 years.

Still worse, as Knights successors such as Poul Harremoes and colleagues have pointed out (The Precautionary Principle in the 20th Century, Earthscan, London, 2000), are situations of ignorance. Here you dont even know all the things that might go wrong, much less the probability of their causing harm. For example, before 1974 no one knew that CFCs could cause ozone layer damage.

Obviously, this ignorance would have invalidated any attempt, at the time, to calculate of the probability of ozone depletion. Similarly, before 2000, it was not known that the albedo of trees could change a forests effect on global warming; before 2005, how much carbon recently sequestered by land plants is being moved by the Amazon to the oceans and the atmosphere; and before the 1990s, that certain factors including release of methane from ocean floors or the switching off of the Gulf Stream were capable of flipping the earth's climate rapidly from one state to the other.

In situations of indeterminacy, finally, the probability of a result cannot be calculated because it is not a matter of prediction, but of decision. For example, it might be implausible for subsidies for fossil fuel extraction to be removed within five years, but you cant assign a numerical probability to this result, because whether it happens or not depends on politics. In fact, trying to assign a probability to this outcome can itself affect the likelihood of the outcome. In such contexts, the exercise of prediction can undermine itself. Risk, uncertainty, ignorance and indeterminacy each call for different kinds of precaution.

Risk fits easily into economic thinking, because it can be measured. For instance, as Knight pointed out in 1921, the bursting of bottles does not introduce an uncertainty or hazard into the business of producing champagne:

"[S]ince in the operations of any producer a practically constant and known proportion of the bottles burst, it does not especially matter even whether the proportion is large or small. The loss becomes a fixed cost in the industry and is passed on to the consumer, like the outlays for labor or materials or any other. . . This, of course, is the principle of insurance, as familiarly illustrated by the chance of fire loss" (Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1921). Uncertainty, ignorance and indeterminacy, however, call for a more precautionary and flexible, and less numerical, approach. Take the carbon credits to be generated by tree plantations. If these credits were threatened by nothing more than risk, insurance-type calculating techniques would be enough to handle the problem. You could insure carbon credits from a plantation just as you take out fire insurance for a building.

But such credits are characterized not only by risk, but by uncertainty, ignorance, and indeterminacy as well. For example:

*How long will plantations last before they release the carbon they have stored to the atmosphere again, through being burned down or cut down to make paper or lumber, which themselves ultimately decay? This is not simply a risk, in Knight's sense, but involves uncertainties and ignorance that cant be captured in numbers. For example, it is still not known what precise effects different degrees of global warming will have on the cycling of carbon between different kinds of trees and the atmosphere.

*How will plantations affect the carbon production associated with neighbouring ecosystems, communities, and trade patterns? Again, uncertainty and ignorance, not just risk, stands in the way of answering such questions.

*How many credits should be subtracted from the total generated by plantations to account for the activities that they displace that are more beneficial for the atmosphere in the long term, for example, investment in energy efficiency or ecological farming? No single number can be given in answer to this question, since it is inherently impossible to verify what would have happened in the absence of the project. That is, the answer is indeterminate.

By mixing up the analytically distinct concepts of risk, uncertainty, ignorance and indeterminacy, schemes such as the Clean Development Mechanism and Joint Implementation have blundered into what Knight called a "fatal ambiguity".

In this case, it is an ambiguity that undermines the effectiveness of the entire Kyoto Protocol and one that can only be remedied by the suspension of such projects.

---------------------------------------

For more information: http://www.thecornerhouse.org.uk/.

by: ProfMKD @ 9:42 am

|

| CARBON PROJECT Q & A: Carbon Forestry in Costa Rica (fourth in a series)

|

Carbon Forestry in Costa Rica Based on the research of Javier Baltodano, FoE-Costa Rica

Costa Rica has always been one of the countries in Latin America keenest to host carbon forestry projects and other environmental services schemes. In the mid-1990s, looking for new ways to derive value from its forests, it decided to become the first country to bring its own government-backed and -certified carbon forestry credits into the global market, and even before Kyoto was signed was selling them to the Norwegian government and Norwegian and US corporations. To work on the scheme, Costa Rica hired Pedro Moura-Costa, a Brazilian forester with experience on early Malaysian carbon forestry projects backed by The Netherlandss FACE (see earlier blogs in this series) and New England Power of the US. Moura-Costa in turn convinced Societe Generale de Surveillance (SGS), one the world's leading testing, inspection, and certification companies, to use Costa Rica as a test site for learning how to make money as a carbon credit certifier, and on the back of his own experience set up a new carbon consultancy, EcoSecurities. An early Costa Rican project called CARFIX implemented by the voluntary organization Fundacion para el Desarrolllo de la Cordillera Volcanica Central and funded by US Aid for International Development (USAID), the Global Environmental Facility and Norwegian financiers earned its North American sponsors carbon credits by promoting "sustainable logging" and tree plantations on "grazed or degraded lands", claiming to provide locals with

income they would otherwise have to earn through forest-endangering export agriculture and cattle production. Following the emergence of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, Costa Rica pushed for the same certification techniques it had pioneered to be adopted around the globe, and signed further carbon deals with Switzerland and Finland. -- Q. Costa Rica's enthusiasm for carbon offset projects seems to suggest that

there are a lot of benefits in this carbon forestry market for the South, after

all. The enthusiasm is not unanimous, even in Costa Rica. In fact, the boom in carbon

forestry fits into an existing trend of support for monoculture tree plantations

that has aroused much concern among local environmentalists. Between 1960-85,

about 60 per cent of Costa Ricas forests disappeared due to cattle farming.

Then there was a wood shortage scare, and the government subsidized

monoculture tree plantations extensively between 1980-1996. Helped by

government incentives, over 130,000 ha has been covered by monoculture tree

plantations over the past 20 years, with the total plantation area in 2000

standing at 178,000 ha (well over three per cent of Costa Ricas territory). The CDM, Costa Rican environmentalists fear, may help spread monoculture tree

plantations even further. In the late 1990s, a government official active in

the climate negotiations helped promote a new law supporting monocultures. Half

of a 3.5 per cent fuel tax went into an environmental service programme

designed largely to give incentives to private landowners to be green in a

country in which 20 per cent of the land is national parks, a few percent

indigenous territories and the rest private land. Under the programme, a

landowner might get, for example, US$90 per hectare per year to conserve

forest, or $500 per hectare over five years to establish a plantation. In

return, the state gets rights to the carbon in the plantation, which it can use

to bargain with in international negotiations. -- Q. How much of this tax money goes to forest conservation, and how much to

plantations? Most payments under the environmental services programme go to forest

conservation, but 20 per cent is used to subsidize monoculture plantations and

agroforestry. This has roused objections from ecologists, academics, indigenous

peoples who argue that monoculture plantations, often lucrative in themselves,

can damage the soils, water and biodiversity that the programme is supposed to

protect. The programme may also soon be supported by a tax on water and

electricity. -- Q. Still, twenty percent is a pretty small proportion, isnt it? Overall, Costa Rica is today putting US$1.5 million annually into financing

4-6,000 ha per year of new plantations. That may not seem much, but Costa

Ricas total territory is only a bit over five million ha. A UN Food and

Agriculture Organization consultants study has suggested that the country set

up even more plantations, up to 15,000 ha per year, using carbon money. Another

study estimates that, during the period 2003-2012, some 61,000 hectares of

monoculture plantations, or 7,600 a year, could be established in so-called

Kyoto Areas. Thats well above the current rate,3 implying that plantations

could start competing aggressively with land that might otherwise be given over

to secondary regeneration and conservation of native forest. In addition, because CDM forestry projects, for economic reasons, would probably

have to cover 1000 ha and up (see below), they could well threaten the land

tenure of people carrying out other forest projects in Costa Rica. The average

landholding in the country is less than 50 ha, with most parcels belonging to

families, although of course huge corporate farms also exist. Land

concentration in connection with monoculture tree plantations is a familiar

phenomenon from around the world, including areas of Costa Rica where pulpwood

plantations have been set up.4 -- Q. But again, sacrifices do have to be made for the climate, dont they? Ironically, one of the things that the Costa Rican case reveals is the

impossibility of determining whether the climate in fact would benefit from a

policy of pushing such projects or even of fulfilling the conditions set out

in the Kyoto Protocol and the Marrakech Ministerial Declarationv for

reforestation and forestation carbon projects. Take, for example, a study on carbon projects done by the Forest and Climatic

Change Project (FCCP) in Central America, jointly executed by the Food and

Agriculture Organization of the UN and the Central American Environmental and

Development Commission (CCAD).vi Research done for the FCCP report shows that available soil use maps are not

precise enough to show how carbon storage in prospective carbon sink areas (or

Kyoto Areas) has changed since the 1990s, and are also hard to compare with

each other. That would make accounting for increased carbon storage over the

period since then impossible. The studys conclusions also suggest that it would be impossible to show to what

extent Kyoto carbon projects were additional to those that the country

implements as part of its forestry development projects: it is not possible

to predict in what exact proportion these activities will be in or out of the

Kyoto Areas and any assumption in this respect is enormously uncertain. In

addition, Kyoto carbon projects could find it hard to factor out the

anthropogenic activities to encourage natural seed nurseries that are being

promoted and funded without carbon finance. One example is landowners

protection of their lands against livestock and fires that has been paid for

since 1996 by the National Fund for Forestry Financing (FONAFIFO). The FCCP study reveals, above all, the tensions between accounting convenience

and accuracy in measuring carbon. For example, it considers that measurements

of soil carbon before and after the start of any carbon forestry project would

be too costly, even though such measurements are widely held to be a key to

carbon accounting for plantations, which disturb soil processes

considerably.vii Similarly, the study accepts for convenience a blanket carbon

storage figure of 10 tonne/ha for grassland sites that could be converted to

carbon forestry. However, Costa Rica boasts too wide a variety of grasslands

and agricultural systems most of them comprising a lot of trees for such a

figure to be used everywhere.viii --Q. But cant you cover such unknowns just by taking the amount of carbon you

think you might be sequestering and reducing the figure by a certain

percentage, just to be on the safe side? Thats what many carbon accountants do. The FCCP study, for example, suggests a

20 per cent deduction from the figure designating total potential of carbon

sequestered to compensate for political and social risks and a 10 per cent

deduction to compensate for technical forestry risks. The problem with such risk-discounted figures is that carbon sequestration is

characterized by far more than just risk. This goes back to a distinction first

made by the economist Frank Knight 80 years ago between risk and uncertainty

(see succeeding blog: Global Warming and the Ghost of Frank Knight). In situations characterized by risk, all possible outcomes are known in advance

and their relative likelihood expressed as probabilities. In such situations,

it makes sense to talk about margins of error and safe levels of

discounting. Where the probabilities of outcomes are unknown, however, youre faced with a

situation of incalculable uncertainty. The situation is even more serious when not even all the possible outcomes are

known. Such conditions of uncertainty and ignorance, and not simply risk, are

the typical realities that biological carbon accounting has to cope with. In

these conditions, its impossible to be sure whether any particular numerical

risk factor is conservative enough to compensate for the unknowns involved. In Costa Rica, for instance, most monoculture tree plantations are less than

twenty years old, with a trend toward planting just two species Gmelina

arborea and Tectona grandis. Pest or disease epidemics can therefore be

expected, but their extent is incalculable at present. Furthermore, El Niño

climate events may propagate enormous fires whose extent, again, cannot be

calculated in advance. During the dry season of 1998, in the humid tropical

zone where uncontrollable fires had never been reported before, over 200,000

hectares were burned. Part of this territory is under monoculture tree

plantations. Given such realities, its unsurprising that the FCCP carbon

project study could give no reasons for its low technical risk figure of 10

per cent. There is in fact no scientific basis for the assignment of any such

number. At present, there is also little basis for guessing how much carbon sequestered

in Costa Rican trees will re-enter the atmosphere and when. The FCCP study

simply assumes that 50 per cent of the carbon sequestered by a given project

will remain so once the timber has been sold and used. However, the most common

plantation species in the country (Gmelina arborea) is logged at least once

every 12 years and most of the timber is used to manufacture pallets to

transport bananas. The pallets are thrown away the same year they are made and

probably though no one has done the empirical studies necessary store

carbon no longer than a few years. The FCCP study also assumes that anthropogenic activities to foster natural seed

nurseries will result in secondary forests that will be in place for at least 50

years. Accordingly, they make no deductions for re-emission of carbon. However,

although current forestry law prohibits transforming forests into grasslands,

both legal changes and illegal use could result in large re-emissions whose

size would be impossible to determine in advance. -- Q. It seems that one of the big problems with doing the accounts for forestry

offset projects is that you cant store carbon permanently in trees. The impermanence of tree carbon isnt necessarily itself a problem, but rather

the fact that you cant verify how impermanent it is. Everyone knows that the carbon stored in trees has a different lifespan from the

carbon left underground in coal, oil and gas deposits. Over historical time

spans, the carbon in fossil deposits will stay pretty much where it is unless

somebody disturbs it. You dont need to worry too much about it leaking out to

the atmosphere. But once carbon enters the above-ground system consisting of

the air, oceans, trees, grass, soil, fresh water, and so forth, things change.

No part of the above-ground pool of carbon can be permanently separated from

the atmosphere. It belongs to a system in which carbon is always cycling into

and out of the air in hard-to-predict ways. So when you try to sequester this carbon in trees to separate it from the

atmosphere you know this separation is going to be temporary compared to the

separation between underground fossil carbon and the atmosphere. Eventually the

carbon in the trees is going to go into the air. The only question is when. The

carbon in grass or a tree trunk, in the top seven inches of soil, in furniture

or paper or a cigarette, may all be separated from the atmosphere for a while,

but in a way much harder to predict than the way the carbon in coal deposits a

kilometer underground or in carbonate rock dozens of kilometers beneath the

surface is separated from the air. To put it another way, fossil carbon flows

into the biosphere/atmosphere system are essentially irreversible over

non-geological time periods, while those from the atmosphere into the biosphere

are easily reversible and not easily controlled. But storing carbon for even a short time in biological systems can still delay

carbon buildup in the atmosphere and therefore delay climate change. So

biological carbon, even though temporary, is still highly relevant to climate

change and should be preserved wherever possible. Accordingly, carbon forestry

projects neednt be permanent to be useful. -- Q. Exactly! So why cant we just figure out how much temporary carbon storage

in trees is equivalent to keeping X amount of fossil fuels in the ground? Thats the unjustified leap that many technicians and politicans make. They

assume that just because trees are good for climate, there has to be a way of

measuring how many trees equals, in climatic terms, how much fossil fuel

emissions. The officials and diplomats responsible for the CDM, for example, have committed

themselves to the claim that a world that closes a certain number of fossil fuel

mines ought to be equivalent to a world that leaves them open but plants a

certain number of new trees. They have embedded in the Kyoto Protocol the

doctrine that planting a certain number of trees can make industrial emissions

"climate-neutral" or carbon-neutral. What has arisen is what scholar Eva Lovbrand calls a political requirement to

determine the long-term fate of carbon stored in biomass and soilsxi and to

commensurate it with underground fossil carbon. To meet this politics,

technicians have been busy coming up with accounting methods for trying to

tackle the problem that carbon stored in trees may be re-emitted to the

atmosphere at any time. The Global Change Group of the Tropical Agronomic Centre for Research and

Teaching (CATIE), for example, has been assessing ways of putting non-permanent

biological carbon in the same ledger with fossil carbon emissions, so that the

two can be added and subtracted, in ways relevant to Costa Rica and Central

America. -- Q. It sounds like a great idea. Whats the problem? Well, lets look at one proposal for biological carbon accounting surveyed by

CATIE. This is tonne-year accounting. The first step in tonne-year accounting is to determine the period that a tonne

of carbon has to be sequestered in order to have the same environmental effect

as not emitting a ton of carbon. Because the lifetime of greenhouse gases in

the atmosphere is limited, this time period should be finite. If the

equivalence factor is set at 100 years, then one tonne of carbon kept in a

tree for 100 years and then released to the atmosphere is assumed to have the

same environmental effect as reducing carbon emissions from a fossil-fuelled

power plant by one tonne. The second step is to multiply the carbon stored over a particular year or

decade by the complement of this equivalence factor to find out what the

climatic benefits are of that project for that year, and to limit the carbon

credits generated accordingly. So the forestry project doesnt have to be

permanent to generate carbon credits, it will just generate fewer credits the

more short-lived it is. -- Q. You still havent mentioned any problems. The first problem is that you still have to measure the carbon stored by a

project over a particular year or decade. That runs into the same problems with

ignorance, uncertainty and all the rest mentioned above. Second, no one knows

how long the equivalence time should be. Figures ranging all the way from 42

to 150 years have been mentioned.xiii Another difficulty is that even if one

settles on a figure of, say, 100 years, it does not necessarily follow that

carbon sequestered for ten years will have 10/100th of the climatic effect of

being sequestered for 100 years. Again, the problem is not that any given patch

of trees is temporary, but that theres so much uncertainty and ignorance about

how to measure its relevance to climate. Its not a matter of calculable

risk, but something far more recalcitrant to market accounting. In addition, tonne-year accounting can make what allowances it does make for

uncertainty only at the cost of generating carbon credits very slowly. That

makes it unattractive to business. It also militates against small projects.

The CATIE study found that at prices of US$18 per tonne, the tonne-year

methodology allows for profitability only in projects of over 40,000 ha. -- Q. Arent there other possible accounting methods? CATIE surveyed several, but they all run up against similar problems of

uncertainty, scientific ignorance and the impossibility of reconciling cost and

verifiable climatic effectiveness. For example, a method called average storage adjusted for equivalence time

(ASC) gives you more credits more quickly, but only at the cost of making

unwarranted assumptions about how long biological carbon can be verifiably

sequestered. Then there are the UNs temporary CERs, which expire at the end of the Kyoto

Protocols second commitment period and must be replaced if retired for

compliance in the first commitment period; and long-term CERs, which expire

and must be replaced if the afforestation or reforestation project is reversed

or fails to be verified. These beg the question of how such credits are to be

verified in the first place and also involve complex accounting and high

economic risk to business. In the end, CATIE came to the conclusion that CDM forestry projects had to be

big in order for it to be worthwhile to fulfil all the accounting and other

requirements. Out of a total of over 1500 simulated scenarios, only eight per

cent made it possible for projects under 500 ha to participate. The mean size

of a project for the sale of carbon to be profitable was 5,000 ha. One way out

would be to bundle smaller projects together and employ standardized

assumptions and procedures, but again that would magnify accounting mistakes

and also would be hard to achieve given the Costa Rican land tenure system. -- Q. Youve talked a lot about how much harder it is to measure how much carbon

is sequestered in tree projects than simply to keep fossil carbon in the ground.

But maybe we dont need to compare carbon sequestered in trees with carbon

stored for the long term in fossil deposits. Isnt it true that about a quarter

of the excess CO2 in the atmosphere comes from deforestation? The atmosphere

doesnt care whether its carbon dioxide has come from burning coal or from

burning forests. We should think of forestry carbon projects like Costa Ricas

as replacing carbon released from forests, not as replacing carbon released

from fossil fuel combustion. The point of carbon forestry should be to help

stabilize biospheric carbon releases to the atmosphere by returning more carbon

from the air to the land, not to compensate for fossil fuel use. This should

solve the measurement problem, since all we have to do is compare biotic

carbon with other biotic carbon. No, that has no effect on the measurement problem. Its impossible to quantify

verifiably the effect any particular forestry project has on the climate,

whether the project is taken to be compensating for fossil fuel burning or

compensating for forest destruction elsewhere. What makes comparison between biospheric and fossil carbon impossible is that

the whole above-ground carbon system is fluid, with relatively weak boundaries

between trees, atmosphere, water and so on, compounded by the inclusion of all

these things within social systems. Unfortunately, the same characteristic

fluid boundaries and entanglement with social systems also makes it hard to

verify how much carbon is being saved as a result of a particular project, and

thus whether a project is changing the balance of the above-ground carbon

complex. Yes, climate change can be addressed by trying to conserve forests just as it

can be addressed by keeping fossil fuels in the ground. But it cant be

verifiably addressed by burning forests and then compensating for this

burning with biospheric projects any more than it can be verifiably addressed

by mining fossil fuels and then compensating for their transfer to the

biosphere with biospheric projects. -- Q. Whats the future for Costa Rican carbon forestry projects? The government has recently declared that it will put more effort into

non-forestry projects such as windmills and hydroelectric schemes on the ground

that they are less complicated and yield higher-priced carbon credits. On the

other hand, companies such as the US-based Rainforest Credits Foundationxiv

continue to be eager to set up new carbon schemes in Costa Rica, often without

much prior consultation with the government.

-----------------------------------------

From a compilation being produced by the Dag Hammarskjold Foundation, Uppsala,

Sweden. For further information: larrylohmann@gn.apc.org.

by: ProfMKD @ 9:38 am

|

|